R005

R005

Husband: Lewis Edward Wood

Father: Francis Marion Wood [R004]

Mother: Rebecca (Entsminger) Wood [R004]

Born: 12/18/1856, Collierstown, Rockbridge County Va. [S003].

Died: 5/8/1948. Buried at Horeb Baptist Church, Bath County.

Wife: Emma Katherine (Burger) Wood

Father: William Crawford Burger [R500]

Mother: Katherine Ann (Miller) Burger [R500]

Born: 8/6/1860, “Old home, Stewart Creek” [S003]

Died: 11/10/1928, at Nimrod Hall. Buried at Horeb Baptist Church, Bath County.

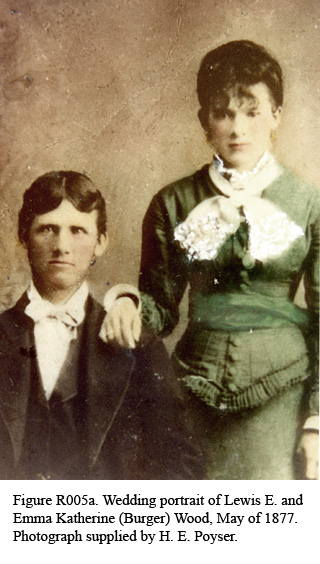

Married: 5/10/1877, at the home and birthplace of Emma Burger on Stewart Creek, Bath County (Fig. R005a) [S003]. John M. Pilcher, Minister. (Lewis and Emma were delighted in 1923 when, after all those years, Rev. Pilcher visited them at Nimrod [S089]. He died two years later.)

(2011) These partners called one another “Edward” and “Emma,” but he seems to have been known elsewhere as “Lewis,” or more commonly “Mr. Wood.” He was called “Mr. Wood” so consistently around Nimrod that even my mother referred to him by that name.

Lewis Edward Wood was born on December 18 1856 at the home of his mother’s parents in Collierstown, Rockbridge Co., Va., and was named after both of his grandfathers. He was brought to his parents’ home, the “White House,” [R020] in Bath County when three weeks old [S003].

Lewis was seven years old when his father died in the Civil War. During the war, when news came of approaching Union raiding parties his mother would assemble her children and livestock, hide their valuables or pack them in a wagon, and flee to a hidden mountain hollow [S021]. As the eldest son, much of the responsibility in these maneuvers fell to Lewis. He described to Janis LaRue a technique of looping a willow switch around the muzzle of the horse he was holding, which prevented it from answering the neighs of horses in passing Union patrols [S007].

Lewis’s widowed mother married James F. Reynolds in 1864, when Lewis was eight. Presumably the family continued to live in the White House thereafter, though I don’t know this for certain. In 1877, at age 21, Lewis married Emma Katherine Burger, then 17, at her home and birthplace on Stewart Creek (Fig. R500b), which is north of Millboro Springs (the maps now spell it Stuart Creek). There had already been another, parallel, marriage between the two families: four years earlier Lewis’s sister Martha married Emma’s brother Samuel Crawford Burger [R450].

During his upbringing Lewis had acquired enough of an education to be qualified to teach school in the County: on his marriage license Lewis gave as his profession “schoolteacher,” though it is likely farming also filled much of his time. Apparently Lewis and Emma lived at first with his mother and stepfather in the White House; their first child (Kemp, 1878) was born at the “Wood home near Sitlington” [S003]. Their next child (Mill, 1880) was born at Emma’s parents’ home on Stuart Creek. In 1881 Thomas Sitlington [R521] died, and Lewis and Emma moved into the Sitlington homestead, two miles NE of the White House; they had contracted to manage the property and tend the needs of Thomas’s widow Mary, 72 [S072]. Emma was the granddaughter of Thomas Sitlington’s first cousin Martha (Crawford) Burger [R505]. The only furniture they took with them was a single chair. [R521] contains a wonderfully graphic description by Kemp Wood of their life at the Sitlington Stone House. Lewis and Emma remained at the Sitlington homestead until ~1887. The Wood family Bible [S003] says their next three children were born simply at “Sitlington.”

Lewis and Emma’s first five children were:

David Kemper, 3/6/1878-1/12/1973 [R550]

Millard Kenny, 7/20/1880-2/8/1957 [R551]

Mary Lillian, 9/7/1882-7/24/1944 [R552]

Edward Manning, 7/10/1884-9/15/1951 [R553]

Katie Young, 7/18/1886-1/27/1963 [R554]

In this period Lewis and his brother and sisters reached adulthood and received title to the land holdings of their deceased father, Francis Marion Wood. Each child received one undivided fourth of the land (i.e., one-fourth interest in the whole estate; not a specifically carved-out fourth of the land). They promptly sold their bequests, but the transactions were not straightforward. Lewis’s sister Mattie (21) and her husband Samuel Crawford Burger [R450] sold their share of tracts B, C, D, and F in Fig. R003a, aggregating 986 acres, to Matthew Surber for $500 in 1876 (DB13-114). Lewis Edward (24), James (22), and Lucy (18) and her husband George Dill sold their shares of the same tracts to Surber for a total of $600 in 1880 (DB16-84). This leaves unresolved what happened to tract A in Fig. R003a, Edward Wood’s first purchase in Bath County (DB4-61, DB4-208), which included the White house; and the 150 acres Edward Wood purchased from W. Keyser and J. Brinkley in 1816 (DB5-218). Tract A had already diminished from 208 to 125 acres when Francis Marion Wood received it in 1854 [R904]; the tract described in [R904] shows the NE portion of the original 208 acres missing, and I speculate that it had been sold or otherwise conveyed to Francis’s sister Elvira (Wood) and her husband John Armentrout [R352], who lived on the NE edge of Tract A. The situation is more complicated than I have described; further transactions involving the Francis Marion Wood estate, which as yet defy my understanding, appear in DB15-281 and DB15-373.

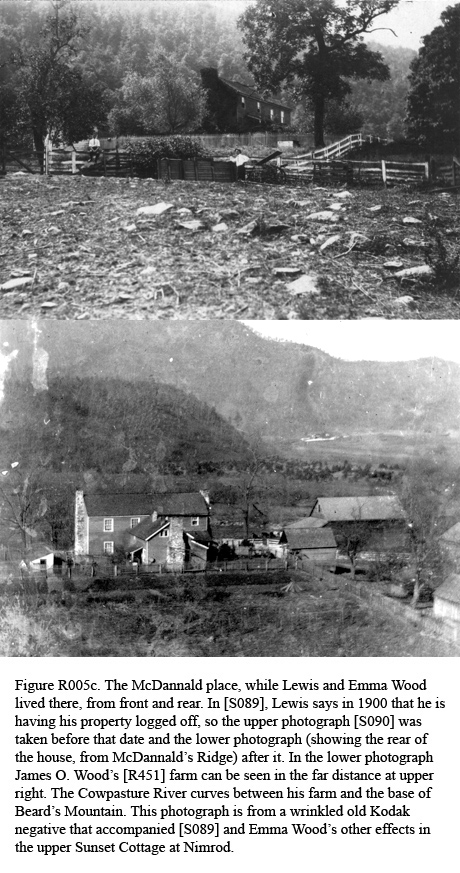

Sometime between 7/18/1886 and 1/11/1888 (going by the birth dates in the family Bible) Lewis moved his family to a rented or lent house ~3.5 miles NE (upstream) of the Sitlington house. Early photographs of the house are shown in Fig. R005c, and its location is indicated in Fig. R005b. On 4/24/1888 the land that Lewis was living on, which had belonged to Samuel McDannald and his descendants, was forfeited in a legal action; the property (943 acres) was put up for public auction on the front steps of the Bath County Courthouse. Lewis Edward Wood and James A. Crizer of Clifton Forge jointly bid on the property, and purchased it for $6900: only $256.06 down, the rest in three equal installments with interest, to be paid over the next three years (DB19-317).

However it appears to have taken Wood and Crizer longer than three years to pay for their land purchase, because the deed for the land was not conveyed to them until December 18 1900 (DB19-330). Two days later (12/20/1900) the two partners reappeared in court, and legally divided the tract of land between themselves. The division is shown in Fig. R005b. Lewis (then 44) got the portion of land that lay farthest SW, 438 acres, which included the house his family was living in. A few months before the division Crizer had sold his half of the property, which extended NE almost to the Van Lear place [see R581], to Susie E. and J. N. Kames.

All the rest of Lewis and Emma’s children were born in the house on this property; a family group is shown in Fig. R005d:

William Burger, 1/11/1888-10/21/1981 [R555]

Russell Guy, 10/24/1889-4/16/1960 [R556]

Cecil Karl, 11/9/1891-7/29/1948 [R557]

Edith Duval, 12/6/1893-12/6/1990 [R558]

Mattie Jane. 11/19/1895-9/14/1962 [R559]

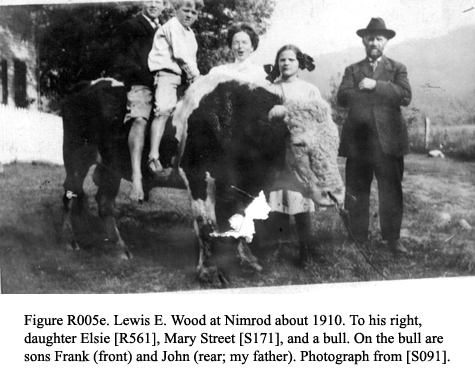

John Armstead, 11/22/1897-2/19/1976 [R560], see Fig. R005e

Elsie Marie, 2/10/1899-11/24/1986 [R561], see Fig. R005e

Shelby Lee, 7/2/1900-10/17/1900 [R562]

Francis Marion, 7/4/1902-10/4/1980 [R563], see Fig. R005e

My father, John Armstead, always referred to this house as “the old home place.” Here are two brief remembrances from Kemp Wood’s diaries [S074]:

“MAY 31 1950 Flood of 1889.

Generally referred to as the Johnstown Flood. As a boy 11 years old this scribe remembers the same flood. It covered the bottom land of our farm & washed away or covered up all crops -- corn, wheat, oats, even carried soil away deep as plowed. Dad remarked, as he watched the turbulent waters, ‘Boys, we’ll have farms on the Mountain side. Result -Peach & Apple orchard on top of mountain. What delicious peaches too.

“DECEMBER 25 1951 CHRISTMAS LONG AGO

In the mountains- a foot or more of snow- ice on the roads- sleet, snow and ice on the trees, sparkling in the sunlight like millions of glistening diamonds. A roaring fire in the open fireplace before daylight- pulling down the stockings stuffed with fire crackers, a big orange, an apple, stick candy and nuts. Crackers fired outside before day- a rabbit hunt- home for a big dinner- all the family around the table- happy- glad.”

(My father used to remind me, when he thought my Christmas wish list was too ambitious, that all he got for Christmas when he was a boy was an orange and a jackknife. He never said anything about the firecrackers.)

Lewis and Edward already began having paying guests at the McDannald place: “...The camping folks are still here, and some of them are going to stay until the first of Sep. I certainly will be a happy girl when they are gone, for they are here [I expect this means in the house] all the time most. We are going to board a family of Greys from Richmond, they just have one child, and will be here tomorrow. We will charge the three $12.50 per week. I expect they will stay a month. We have so much company any way it wont make much difference...” (this is from a letter from Katie to Kemp, 8/6/06 [S089]). And Lewis’s farm was a supplier of produce to Nimrod Hall, which was a major economic presence in the neighborhood. So perhaps logically, Lewis’s next step was to buy Nimrod, in 1907, when it came on the market (DB23-214). In the same year Lewis sold the family’s “McDannald Place” home and farm to Jasper G. Crizer, a son of James A. Crizer [S073]; thereafter it came to be called “the Crizer place.”

Nimrod Hall was (and is) a stately hilltop house and summer resort with a view commanding the countryside, ~2 miles NE of the McDannald place; it is described in [R021]. Lewis was 51 and Emma 47 when they made the move. They lived there for the rest of their lives. Lewis enlarged the Nimrod Hall lands with additional purchases in 1916 (DB28-324) and 1918 (DB31-6). This is only a partial account of his land transactions.

Lewis farmed the Nimrod lands, but his main concern and source of income was Nimrod as a summer resort. (He never seems to have thought of himself as a farmer. Besides calling himself a “schoolteacher” on his marriage license, elsewhere he describes himself as an “innkeeper” or a “postmaster.”) The problems the summer resort business brought him and Emma, centering on occupancy, labor, maintenance, and the weather, are chronicled in [S089]. And of course the problems never ended; the couple had no retirement program. As Lewis and Emma (Fig. R005f) aged, the hard job of running a summer resort became an increasingly unmanageable burden. In 1920 and again in 1924 Lewis, concerned about Emma’s health, tried to sell Nimrod so they could buy a smaller home and relax [see S176], but without success.

Over the years most of their children left Nimrod to make their fortunes elsewhere, there being few opportunities in Bath County. However, Lewis and especially Emma maintained close ties with them. The children organized a surprise family reunion for their parents in 1917 on the occasion of their 40th wedding anniversary; Fig. R005g was taken on that occasion. There was another reunion, this time not a surprise, for the 50th anniversary in 1927 (Fig. R005h); this was the last time they would all be together. For a few years Lewis and Emma relied on (and took for granted) the help of their last three unmarried daughters—Edith, Mattie, and Elsie—to help with the summer work, but in that order they too married and could no longer give Nimrod their first priority. Elsie, the last to marry and the only one to continue residing in Bath County after marriage, was never able to shed her Nimrod responsibilities completely, to the detriment of her own home life [R561].

The other children did little to ease their parents’ labors (exceptions being Frank, the last child who came of age and so the last left at Nimrod; and Burger, who continued to reside in Bath County). However, all of them were always welcomed back, and they came—not only to visit and relax for a week or two in the summer, but to seek solace and material assistance when things went wrong (unemployment, divorce, trouble with the law). Lewis and Emma’s responsibility to their children never seemed to end. The children appear to have given little thought to the additional burden they placed on their parents, who were already overextended.

Emma and Lewis were both diabetic. Emma began a diabetic diet in 1916 (insulin was not available until some time after 1921). Though she must have had a hard time holding to it with the foods available in a farm kitchen, she lost weight steadily from the robust figure she displays in Fig. R005d. In the summer of 1925 her left foot became infected, and probably because of delay in treatment and the complications of diabetes her leg had to be amputated below the knee. She spent the winter convalescing at the home of her daughter Kate [R554] in Lynchburg. After that she had a brief respite, during which the photograph in Fig. R005h was taken. It shows a very thin Emma, whose missing leg is artfully hidden behind a flower arrangement. Then in the summer of 1928 she had a cancerous breast removed. She was able to return to Nimrod in the fall, but the cancer had not been excised and she died in November of that year.

About 1930 Lewis, ~75, formally passed the management of Nimrod over to his son, Frank. The transition was probably made gradually, over a number of years, but about that time the Nimrod stationery was changed to read “Frank M. Wood, Manager — Lewis E. Wood, Proprietor.” Lewis survived Emma by 20 years, dying in 1948 at the age of 92. Both are buried in the churchyard of the Horeb Baptist Church, which Lewis helped found. Lewis’s will was designed to make it possible for his son Frank to buy out the interests of the other children in Nimrod Hall, which he did. The will also divided a tidy sum of money among his surviving twelve children, but in the spirit of the Final Accounting we all must submit to he methodically deducted from each child’s share the amount he had advanced to him or her in some past time of trouble.

Lewis was a truly exceptional man. He had a respect for education that none of his children really lived up to, and most fell far short of. Janis LaRue has stressed to me that he assumed a role of leadership in the County, consciously setting a moral and ethical standard for his neighbors, and not hesitating to reproach the latter when they did not meet his standards. Today we would consider such a person overbearing and insufferable, but things were different a century ago, and Lewis was greatly admired and respected. Lewis donated land for a schoolhouse in the Sitlington area, and taught school at various times in his life

[see S093]. Janis’s father, Edward Matheny [R359], was a pupil in his class. About the turn of the century Lewis served as the Superintendent of Schools for Bath County [S072]. Janis remembers that he had an astounding ability to sum a long list of long numbers in his head. Sometimes he did this to amuse her; she would spend a great deal of time setting up a list of numbers and laboriously adding them, then he would come up with the same answer in a few seconds [S007].

Lewis was one of five Trustees who founded the Horeb Baptist Church in 1887. Later he bought an organ for the Church, and a second organ to keep at home for his oldest son, David Kemper, to practice on; Lewis had assigned Kemp the role of organist for the church.

I remember Lewis Edward Wood only as a very old man, thin and erect but infirm, with silver hair and broad moustache (Fig. R005i), who spent his days sitting in a rocking chair on the screened front porch of Nimrod Hall. A Bible was always open on his lap, and a fly swatter was in easy reach. When he did walk it was slowly and painfully, with a cane and feet in heavy white woolen socks and slippers. He seemed stern and penetrating to a small child, and I was terrified of him. He keenly watched the birds and squirrels in the Nimrod yard through the porch screen, though, and occasionally surprised me by talking familiarly of them as “Sammy Jay,” “Blacky Crow,” “Happy Jack Squirrel,” etc. —names of anthropomorphosed animals from the tales of Thornton W. Burgess, which appeared in daily columns in the newspaper he read.

(See also Fig. 459e, in Flodrida.)

Sources: [S003, S007, S072, S074, S089]